Why is foreign policy discourse so dominated by funding-related finger pointing?

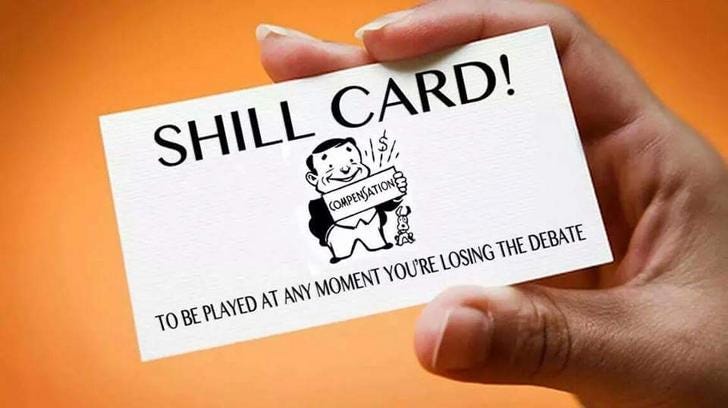

Dismissing a scholar’s work because of alleged financial conflicts of interest is hugely popular

Few mediascapes are as bellicose as foreign policy. In addition to the high financial stakes, primal emotions relating to one’s nationality, ethnicity, and ideology are often stoked. Every protagonist’s favorite retort is accusing the other side of shilling for a foreign government based on a funding link. Ultimately, the reason for the popularity of such claims is the difficulty of deploying modern scientific methods in the formulation of foreign policy arguments.

Foreign policy wonks consider themselves experts on sniffing out financial conflicts of interest when reading their peers’ research, but actually, they are decades behind the game. The natural sciences have been vigilantly – albeit imperfectly – monitoring competing interests long before most DC think tanks were established, most notably in the biomedical sciences.

As anyone who has received a medical bill in the US will attest, health is big business. Accordingly, if you can convince regulators and the general public that your new drug is both effective and safe, it is no exaggeration to say that you can make billions of dollars. A critical step in earning the requisite trust is getting biomedical researchers to test your drug using modern scientific methods.

Inevitably, initial trials are often funded by the pharmaceutical companies that stand to profit from successful findings. This could be as simple as a small grant given to an independent researcher, or as sophisticated as a large, in-house laboratory staffed by dozens of researchers who are the company’s full-time employees.

When the resulting research is peer-reviewed and published, a section of the paper is reserved for the declaration of these competing interests. Crucially – and this is that part that is alien to most foreign policy researchers – a clear conflict of interest does not lead to other scholars nonchalantly dismissing the research and confining it to the intellectual dustbin. Instead, it becomes one of many factors that they take into account when developing their opinions about what does and doesn’t work.

The fundamental reason for this is that they generally don’t have to “take the authors’ word for it”. Other, independent teams of researchers that don’t suffer from the conflict of interest will seek to repeat the original randomized experiment. A couple of successful replications will provide the scientific community with a high level of confidence in the original findings, despite the presence of the conflict of interest.

Admittedly, the system that natural scientists use has many weaknesses, with errors, unconscious biases, and outright fraud being common occurrences. Nevertheless, the manifest superiority of modern medicine over its 18th century antecedent is compelling evidence that this system gets more right than wrong.

As a result, one rarely finds a mainstream media article where one natural scientists dismisses another’s work due to an alleged conflict of interest. Instead, should one scientist doubt the claims made by another – with financial conflicts of interest potentially being the source of that suspicion – they would normally repeat the experiment. Only upon obtaining different results would they write an op-ed, where the failed replication would be the centerpiece of their argument, rather than a lazy appeal about funding sources.

So why is it that researchers working in the area of foreign policy can’t adopt a similar approach? The key reason is the difference in the epistemological properties of each discipline, combined with the difference in target audience of the resulting research.

On the epistemological side, foreign policy in general does not lend itself to experimental methods and randomized control. While a biomedical researcher can randomly separate 100 experimental participants into two groups of 50, assigning one group a drug and the other group a placebo, the same cannot be done with 100 foreign ministers considering whether or not to sign a peace treaty. Scholars working in the field have to rely virtually exclusively on observational data, the interpretation of which is much more subjective than the outcome of a traditional randomized control trial.

For example, physicists can use modern scientific methods to give an accurate prediction of the physical destruction caused by dropping a bomb on a building during an interstate war. However, there is no way to use these methods to develop an accurate prediction of how the government of the country that was bombed will respond to that bomb.

Further, observational data does not lend itself to replication. When an expert gathers data on UK foreign policy and makes an argument based on that data, there isn’t a sense in which an independent colleague working in another country can repeat the exercise to see if they arrive at the same conclusions and use that to test the reliability of the original findings.

Both the original and later attempts at gathering foreign policy observational data are impeded by the inherent secrecy of much of the critical information, which forces researchers to engage in speculation and conjecture. Sometimes, 50 years after the event, a Western government might release transcripts of discussions relating to a foreign policy decision, but when it comes to analyzing present-day policies, policymakers keep their cards close to their chests. The same cannot be said of the viruses and bacteria that a biomedical researcher is investigating.

This leads to the issue of the target audience: whereas academic biomedical researchers are generally speaking to one another, and possibly to technocratic regulators in a government agency, foreign policy experts are generally speaking to policymakers, their aides, and the general public. Most do not possess the intellectual trappings required to comprehend epistemologically advanced arguments, and in the case of senior officials, they don’t even have the time.

Moreover, the phenomena being investigated by the researchers, such as territorial disputes, acts of terrorism, elections, and so on, develop by the minute, and so there is no time for the sort of peer review and replication that allows natural scientists to look past conflicts of interest.

As a result, foreign policy researchers are forced to put out hastily produced research based on partial observational data. This makes the output highly subjective, opening the door for finger-pointing based on appeals to financial conflicts of interest, without the opportunity to use replications to decisively resolve debates.

One also has to acknowledge the somewhat elitist point that the intellectual bar is lower in foreign policy research than in biomedical sciences. Anyone can call themselves a foreign policy expert, and many have studied nothing beyond journalism, and sometimes not even that. This lowers the quality of the discourse, and it is often these subpar self-proclaimed researchers who hyperventilate about funding sources, because they are incapable of engaging the arguments made by their intellectual adversaries.

But even the best of the best cannot overcome the fundamental epistemological challenge posed by the fast-changing and secretive nature of foreign policy decision making. Perhaps if neuropsychology advances to a level that allows us to scan brains and predict complex decisions with a high degree of accuracy, foreign policy analysis will start to look like biochemistry. But until that future materializes, we are stuck with a lot of smug “gotchas”.