There is such a thing as an Arab identity in 2024

Arabs may be fragmented, but the Arab identity is not an illusion

Material comfort is an essential part of our well-being, but so too it is a sense of identity – an answer to the question: who am I? Arabs have been through an identity roller-coaster since the seventh century revelation of the Quran, including the peaks of Arab influence during the early Abbasid Empire, and the valleys of English, French, and Turkish subjugation during the colonial era. My recent visit to the Arab League in Cairo helped me realize that the Arab identity is still alive, albeit in need of rehabilitation.

In 2019, on the eve of Covid-19, I visited Brussels for an academic conference. Having grown up in the UK during the 1980s and 1990s, I had a natural skepticism of the European integration project, reinforced by my never having resided in continental Europe beyond short vacations. However, strolling through the streets of the Belgian capital and interacting with a diverse range of Europeans made me acutely aware of the existence of a European identity, despite the massive cultural differences that exist between countries such as Germany and Portugal, and Czechia and Ireland.

This was no mean achievement given the continent’s long history of internal conflict. Yet the believers who had been working assiduously in the European Commission and its sister institutions since the middle of the 20th century had managed to find real common ground that was distinct from a subscription to generic “Western democratic values”. I had spent 11 years in the US, and it was clear to me how Europeans were a different breed to their brethren from across the Atlantic.

My own identity has been a fluid issue for me to ponder throughout the last four decades. As a citizen of an Arab state (Bahrain) and a son of two Bahraini parents born and raised there, it may seem obvious that I should consider myself an Arab, especially since I have been living in Bahrain since 2012. However, living outside the Arab world for well over half of my life, including all of my childhood, makes the situation more complicated. I could easily classify myself as being more British or American given the many years I spent in both countries, and the profound influence both cultures have had on my own mode of thought.

Naturally, when consciously weighing up which identity one wants to adopt, the perceived success of the various options inevitably has an influence. While the UK has had its recent struggles, overall, its performance over the last three centuries was extremely high. Similarly, the US continues to be the most powerful country in the world. As an economist who really enjoys my field and its history, the intellectual hegemony of Anglo-American economists since the late 18th century serves to enhance my reverence for the two cultures. I also have a strong affinity for Classical Liberal values, many of which continue to influence Western cultures.

On the flip side, Arab countries haven’t exactly covered themselves in glory of late. Pivotal events such as the 9/11 attacks, the US invasion of Iraq, and the chaos during and following the Arab Spring have perpetuated an identity crisis for Arabs, with many understandably questioning whether they want to be associated with a region that has witnessed so much oppression and terrorism. The pan-Arab rhetoric of the middle of the 20th century has become but a distant memory, with multiple refugee crises undermining the sense of solidarity that used to typify life in the Middle East region.

Yet, for family reasons, I returned to the region at a time when many Arabs were forcibly or voluntarily migrating to the West, preparing themselves to gradually surrender their Arab identity as they look to assimilate into new cultures, knowing that their children would likely grow up unable to speak the Arabic language that has come to define our identity. Perhaps driven by a sense of obstinance, my accidental non-conformism resulted in my working extra hard to choose to identify as an Arab. Moreover, over time, living, working and raising a family in Bahrain has served to organically reinforce my decision. Today, I am proud to call myself an Arab, and I feel relief rather than regret that the Western identities I shunned are no more than a source of inspiration and ideas for self-improvement.

Despite this, the socio-political fragmentation that the region has witnessed over the last 30 years has driven a wedge between feeling like a Bahraini and feeling like an Arab, even though Bahrain’s constitution explicitly affirms the country as being Arab. While the Gulf Cooperation Council has had significant success in nurturing the Gulf identity, broader efforts at regional integration have not made as much progress, making me doubt the Middle East’s ability to replicate the European identity that had so tangibly revealed itself to me in Brussels in 2019.

A recent experience suggested that tales of the Arab identity’s demise may be premature. During February 2024, I was fortunate to be part of a Bahraini delegation visiting the Arab League in Cairo. The Secretary General, Ahmed Aboul Gheit, was kind enough to receive us in his office, wherein I got my first Arab jolt: he showed us all of the artistic works the Arab League had received from its member states, including many beautiful specimens from across the region. As he walked us around his office, you could see that he was genuinely proud to have the honor of being the Secretary General of the League that represents all of these artists and their peoples.

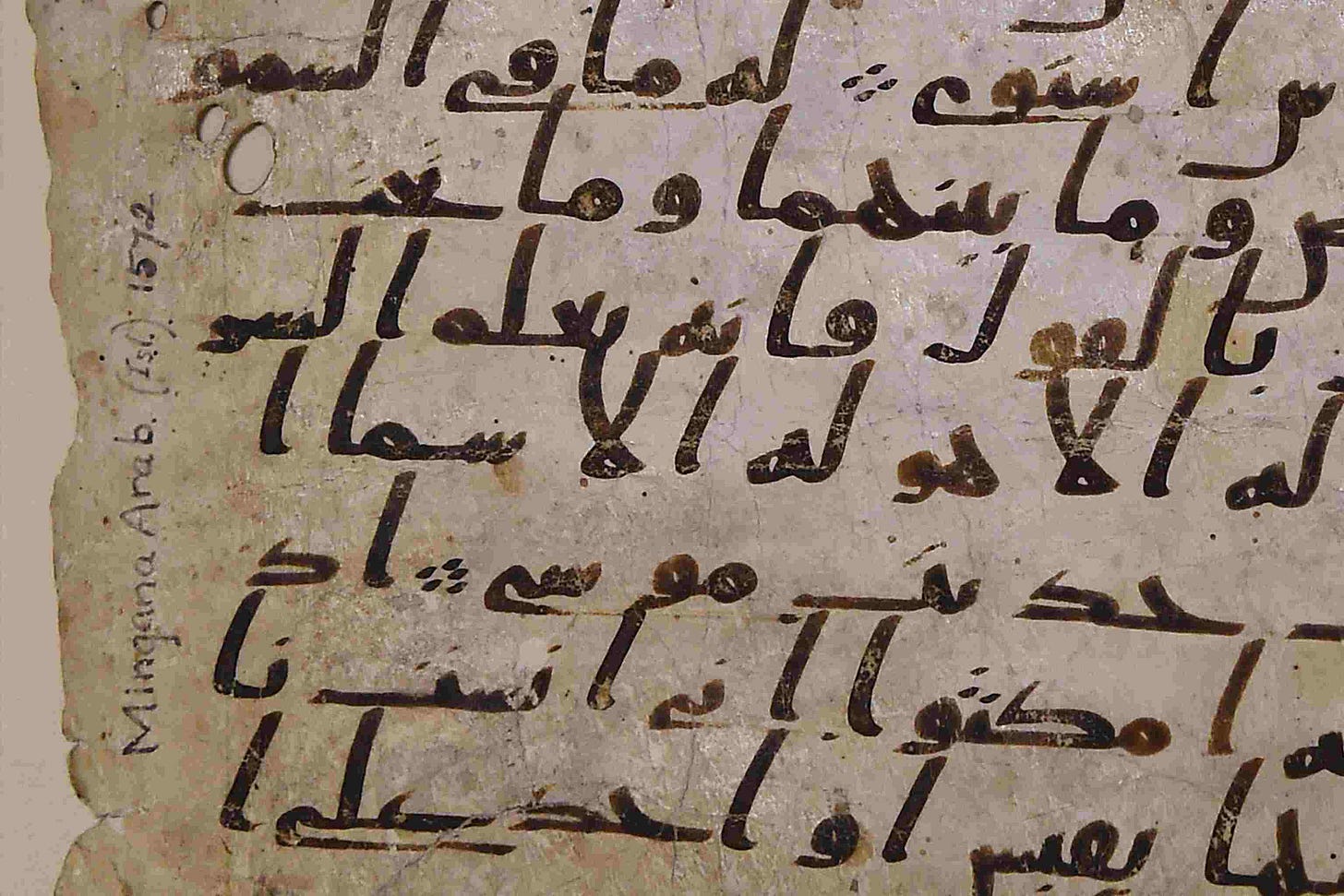

For me, the most moving moment came when he took us to the library and showed us the literary works of the Arab world. While I was impressed by the human oeuvres on display, my attention was immediately seized and maintained by the Quranic verses on the walls of the library, with the most important one being placed on the wall that visitors see as they enter:

ٱقْرَأْ وَرَبُّكَ ٱلْأَكْرَمُ ٱلَّذِى عَلَّمَ بِٱلْقَلَمِ عَلَّمَ ٱلْإِنسَـٰنَ مَا لَمْ يَعْلَمْ

“Read! And your Lord is the Most Generous, Who taught by the pen— taught humanity what they knew not” (96:3-5)

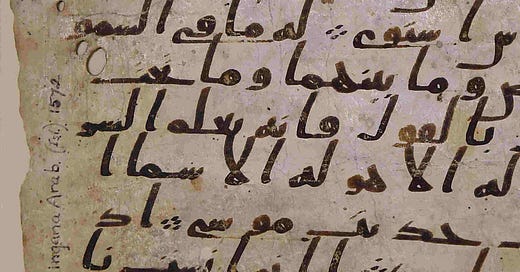

These verses often cause a shiver to run down the spine of Muslims, as they are among the first tranche revealed to the Prophet Muhammad during that fateful night in 609 AD. The context serves to reinforce the power of the words themselves, the command that Allah issued to the illiterate Prophet Muhammad via the Angel Gabriel, despite the Prophet’s protestations that he knew not how to read.

Societies, cultures, and identities come and go. It once meant something to be a Roman, an Aztec, a Phoenician; but no more. No identity can has a right to immortality. However, as long as humans continue to read the Quran, there will continue to be an Arab identity.

إِنَّا أَنْـزَلْنَاهُ قُرْآنًا عَرَبِيًّا لَعَلَّكُمْ تَعْقِلُون

"We have sent it down as an Arabic Quran so you people may understand / use reason" (12:2)

To me, the Quran is what anchors the Arab identity. Language is always an essential part of any identity, and this is accentuated in the case of Arabic, because the Quran was revealed in Arabic, and because altering the Quran is among the gravest of sin for Muslms, meaning that the language will continue. If I pick up an English text from the 9th century, I can barely understand 10%; yet in Arabic, I can understand almost all of the text. The language’s longevity and association with the divine verses of the Quran make the Arabic identity unique, and the Arab League’s library had brilliantly seized upon this in the way the decorated their walls. No matter how much the Arab world underperforms, Arabs will always be able to take solace in their command of the language of the Quran.

My personal, subjective characterization of what it means to be an Arab raises important questions about non-Muslim Arabs, and non-Arab Muslims. The latter is the easier issue to tackle, as Islam is unequivocal in its embrace of all ethnicities, and its absolute rejection of racial and ethnic discrimination. The homogenous treatment afforded to all in the greater pilgrimage, the hajj, shows this clearly, and during his first and only hajj, the Prophet Muhammad allowed Usama bin Zayd, the son of one of his freed Abyssinian slaves, the honor of riding his camel with him, to affirm the equality of all to the largely Arab crowd that was walking to Makka with him.

To me, anyone who is willing to embrace and revere the Arab language, and to learn to speak it fluently, and to appreciate its integral relationship with the Quran, is an Arab, regardless of their genetic links to the region. This is a loose analogue to the process of naturalized citizenship we see in the Western world today, most notably the US, where someone voluntarily adopting the cultural values of a certain country, and living it for a sufficient amount of time, is granted equal rights and recognition to those who already have citizenship. Note that to me, the distinction between an Arab and a Muslim is that the latter can believe in the divinity of the Quran and memorize the verses needed to practice the religion without ever having a command of the language.

The issue of non-Muslim Arabs is much more complex, and I won’t pretend to have any insights. Technically, it is possible for a Christian or atheist to afford the Arabic language a greater level of appreciation than other languages because of its association with the Quran even if they do not believe in the Quran’s divinity. However, I don’t know if it is as easy for a non-Muslim Arab to revere the Arabic language in the way that Muslim Arabs do, which I regard to being so fundamental to the Arab identity.

However, as an Arab, it is not just incumbent upon me to celebrate what makes me proud of my identity; I also have to acknowledge the areas for improvement. I have written a lot about this on my Substack and elsewhere. Some of the most salient weaknesses are in conflict management, where Arabs have a poor track record at the inter-personal, inter-organizational, and international levels. Another key problem is the continuing scourge of ethnocentrism and tribalism, which drives Arabs to commit grave transgressions in the name of the sub-group whom they identify with, despite Islam putting firm limits on the extent to which one should favor one’s kin over others.

Yet, after my return from Cairo, and as I write this essay, I still feel positive about the future. Artificial intelligence, climate change, and many other phenomena have induced great fear among people across the entire globe. As an Arab fluent in the language of the Quran, I will always retain a sense of optimism, and maintain a deeply-set anchor that makes me feel confident that I know who I am and what makes me different to others.